dialectic

noun di·a·lec·tic \ˌdī-ə-ˈlek-tik\

1: philosophy: a method of examining and discussing opposing ideas in order to find the truth

2a: discussion and reasoning by dialogue as a method of intellectual investigation; specifically: the Socratic techniques of exposing false beliefs and eliciting truth

4a: the Hegelian process of change in which a concept or its realization passes over into and is preserved and fulfilled by its opposite.

5a: Any systematic reasoning, exposition, or argument that juxtaposes opposed or contradictory ideas and usually seeks to resolve their conflict

6: the dialectical tension or opposition between two interacting forces or elements(Merriam Webster Dictionary)

To me, this word is at the heart of Jane’s experience as a character. The clash of opposing ideas, the search for truth behind pretense is everywhere in her words and in Brontë’s narrative. Rich and poor, beautiful and plain, passion and self-control, innocence and experience, consistency and spontaneity, madness and sanity, cultivation and vulgarity, male and female, conventional female and proto-feminist, appearance and reality: this is the stuff of Jane’s life.

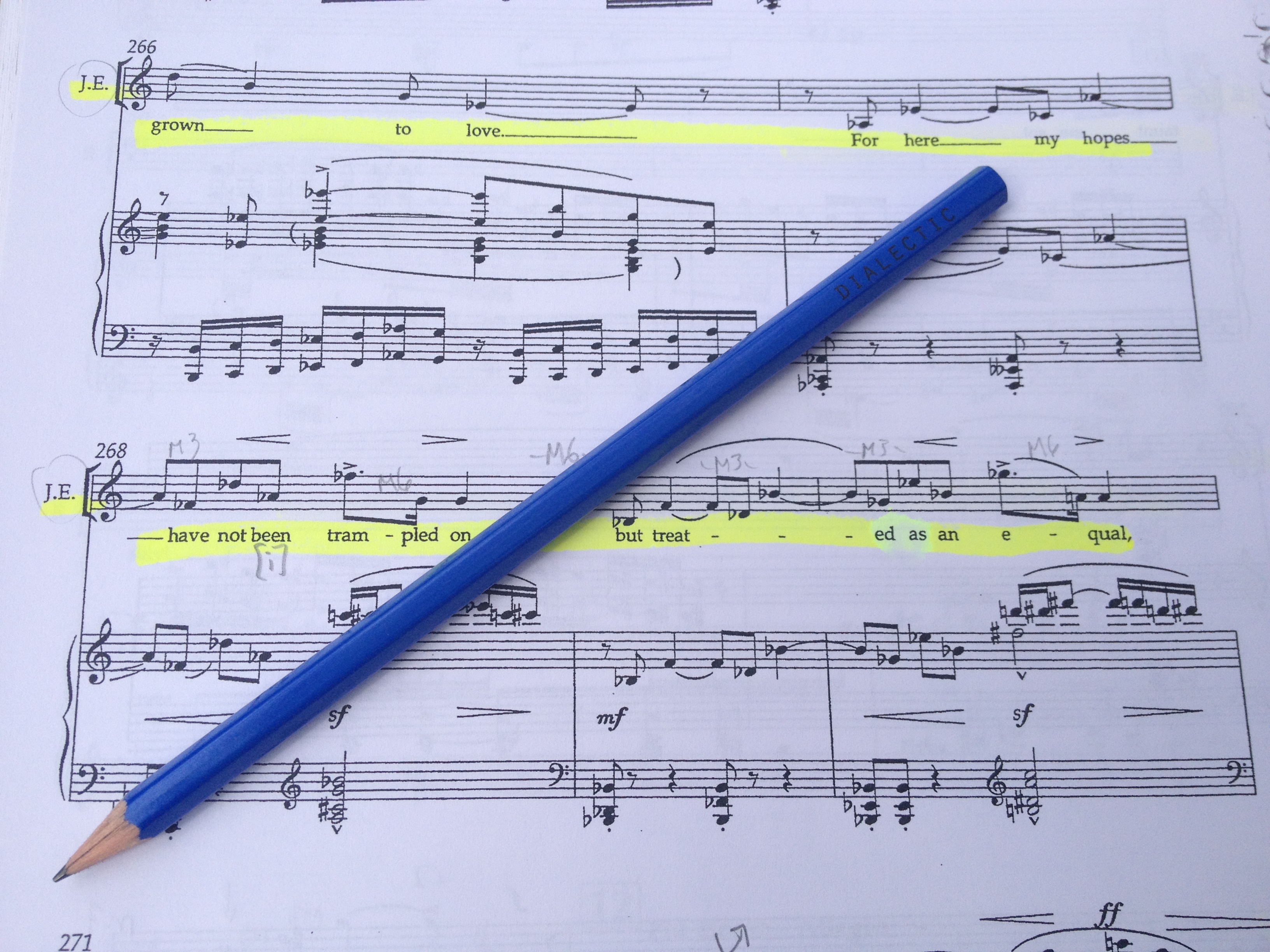

John Joubert captures these tensions and dialectics beautifully in syncopations and many, many wide leaps in Jane’s vocal line, not wayward but carefully crafted, often in sequences, to mirror the veneer and habits of self-possession she has acquired at such cost:

I was quiet; I believed I was content; to the eyes of others, usually even my own, I appeared a disciplined and subdued character. (Ch 10, p.86).*

In many ways, this novel and opera are about the ways in which, sometimes to her surprise, sometimes to others, the intensity always present beneath that calm surface erupt in both speech and action. In a sense, her desire is simple: to love and be loved. Raised as a resented intrusion into her aunt’s household, she found not love but constant, profound injustice, both there and at Lowood.

Kenneth Birkin’s excellent libretto deftly splices exact quotations with succinct, elegant summaries, poetic in their own right, of expansive and discursive passages, capturing in a few lines the spirit and tone of whole chapters. A case in point is Jane’s confrontation with Mr. Brocklehurst before her departure for Thornfield, an event not contained in the novel but which serves as a dramatic exposition of chapters 1-10 in a single scene:

My childhood needs were never met,

Fostered by grudging hands on charity.

I was unwanted, cast aside,

Denied a parent’s love and care,

Taunted, beaten, treated cruelly,

I learned to school my own rebellion,

Yet my anger grew, turning to stubbornness,

As jealous lies, unfounded calumnies followed me here

To where your punishments and dire deprivations

Brought death and disease.

Remember Helen Burns, my dearest friend.

Where is she now? I mourn her still.

It was you, sir, you are accountable!

It was your negligence.

Predictably, Brocklehurst denies culpability, adjuring her instead that hard as life at Lowood has been, he was but following her aunt’s orders, that

This charity you spurn, Miss Eyre,

brought present opportunity;

has made you what you are.

She rounds on him, replying,

That was convenience, not charity.

My aunt relinquished long ago all interest in my affairs.

I am my own mistress now!

Here one of the great themes emerges which Birkin and Joubert chose to emphasize: the innate equality of men and women. Birkin has cleverly spliced together exact quotations with elegant summaries of longer expositions by Brontë. She first sounds the theme in Chapter 10, after the departure of Jane’s beloved Miss Temple from Lowood, when she suddenly looks beyond the school walls for the first time in 8 years:

My world had for some years been Lowood: my experience had been of its rules and systems; now I remembered that the real world was wide, and that a varied field of hopes and fears, of sensations and excitements, awaited those who had courage to go forth into its expanse, to seek real knowledge of life amidst its perils. (Ch 10, p.86)

She looks afresh at the microcosm that has been her world, finding it wanting:

I had had no communication by letter or message with the outer world: school-rules, school-duties, school-habits and notions, and voices, and faces, and phrases, and costumes, and preferences, and antipathies: such was what I knew of existence. And now I felt that it was not enough: I tired of the routine of eight years in one afternoon. I desired liberty; for liberty I gasped; for liberty I uttered a prayer; it seemed scattered on the wind then faintly blowing. I abandoned it and framed a humbler supplication; for change, stimulus: that petition, too, seemed swept off into vague space; ‘Then,’ I cried, half desperate, ‘grant me at least a new servitude!’ (Ch 10, p.87)

Initially, the move to Thornfield does not prove the panacea Jane had hoped; she finds she has indeed exchanged one servitude, one bounded horizon, for another. In Chapter 12, she has settled into her new life, with its new cloistered society of Mrs Fairfax, Adèle and the servants, and she once again finds herself restless, her eye turned ever outwards:

I climbed the three staircases, raised the trap-door of the attic, and having reached the leads, looked out afar over sequestered field and hill, and along dim sky-line–that then I longed for a power of vision which might overpass that limit; which might reach the busy world, towns, regions full of life I had heard of but never seen–that then I desired more of practical experience than I possessed; more of intercourse with my kind, of acquaintance with variety of character, than was here within my reach. I valued what was good in Mrs. Fairfax, and what was good in Adele; but I believed in the existence of other and more vivid kinds of goodness, and what I believed in I wished to behold.

Who blames me? Many, no doubt; and I shall be called discontented. I could not help it: the restlessness was in my nature; it agitated me to pain sometimes. Then my sole relief was to walk along the corridor of the third storey, backwards and forwards, safe in the silence and solitude of the spot, and allow my mind’s eye to dwell on whatever bright visions rose before it–and, certainly, they were many and glowing; to let my heart be heaved by the exultant movement, which, while it swelled it in trouble, expanded it with life; and, best of all, to open my inward ear to a tale that was never ended–a tale my imagination created, and narrated continuously; quickened with all of incident, life, fire, feeling, that I desired and had not in my actual existence.

It is in vain to say human beings ought to be satisfied with tranquillity: they must have action; and they will make it if they cannot find it. Millions are condemned to a stiller doom than mine, and millions are in silent revolt against their lot. Nobody knows how many rebellions besides political rebellions ferment in the masses of life which people earth. Women are supposed to be very calm generally: but women feel just as men feel; they need exercise for their faculties, and a field for their efforts, as much as their brothers do; they suffer from too rigid a restraint, too absolute a stagnation, precisely as men would suffer; and it is narrow-minded in their more privileged fellow-creatures to say that they ought to confine themselves to making puddings and knitting stockings, to playing on the piano and embroidering bags. It is thoughtless to condemn them, or laugh at them, if they seek to do more or learn more than custom has pronounced necessary for their sex. (Ch 12, p. 110-111)

In the confrontation with Brocklehurst, Birkin renders these lines thus:

JE: I am my own mistress now!

Mr B: Now, you are mistaken!

Bondage for bondage is your lot –

A poor exchange, Miss Eyre,

But such is woman’s destiny.JE: No, sir! We are all of us human,

And it is vain to say that we must suffer tranquilly.

Men everywhere revolt against their lot.

We women, too, though secretly,

Condemned by custom to calm,

Feel just as men feel, in like manner and to like degree,

Long for and seek a greater good,

A finer, broader view of life,

Opening new vistas to the captive spirit.

“Cast off your chains.

Essay great deeds and walk in new ways,

Victorious and free.”Mr B: Miss Eyre, control yourself! Such passions suit your station ill.

I see the die is cast—no hep for it—I pity you…Farewell.JE: Prayers done, the girls retire.

Since I promised them, I must wish them good night.

Farewell, my childhood,

So long endured in friendlessness and misery.

Lord, if not happiness,

Grant me, at least, a new servitude.

It is surely no coincidence that the next event in the narration after these reflections if Chapter 12 is the initial meeting with Mr. Rochester on the road, the one who will bring both her greatest joy and, through his deceit, her greatest pain.

*All page numbers refer to my faithful old Penguin Popular Classics edition, 1994.