Having just prepared a large chunk of Ilia from Mozart’s Idomeno with the lovely Kensington Chamber Orchestra, I have been pondering the different demands of singing in Italian and English. Though everyone is always telling me that Italian is easier to sing in, somehow I’d always found it more foreign, not less.

I once asked the wonderful Dominic Wheeler why it felt this way, and he theorized that the music is a reflection of the way the two languages unfold: for the warm Mediterranean languages, he said, the seat of expression is in the vowel, the emotion, so that lines unfold broadly, all in one thought. In contrast, for northern European languages, the seat of expression is in the consonant, and they unfold didactically, a bit at a time, sometimes with the crucial verb at the end.

The link, as Dominic said and David Stout reminded me yesterday, is in how we sing the consonants, incorporating them into the line instead of treating them like obstacles to be negotiated as best we can.

Now what do we mean by ‘line’, a term that both singers and instrumentalists bandy about with great freedom? Well it’s the way that one note connects to another, ideally as seamlessly as possible, so that we perceive a phrase not as single notes or syllables but as one unit of meaning.

To me, a sung Italian line is like a fishing line case, arching out into the air in one gesture, seemingly defying gravity, whereas a sung phrase in English, especially one with lots of syllables, is more like plaiting or braiding, constantly taking separate strands and folding them into and over one another to create that single line. Or like heaving in a rope, hand over hand, always reaching ahead to ensure the rope is both taut and still moving, the ‘sand’ of the breath running through the narrow point of an hourglass.

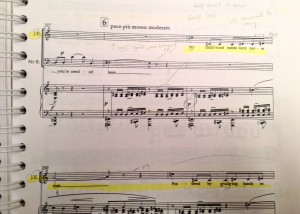

Each consonant is important, needs to be marked and placed and taken care of, given its proper weight. Sometimes this means ‘stealing’ a bit from the note before so that you can slightly elongate it and still land on the vowel on the beat. Take for instance this bit of Jane’s monologue to Brocklehurst in scene 1,

My childhood needs were never met

Fostered by grudging hands on charity

I was unwanted, cast aside,

Denied a parent’s love and care.

The ‘ch’ of ‘childhood’, the ‘n’ of ‘needs’, ‘m’ of ‘met’—all need to come in a split second early, almost rebounding against the end of the previous word to make the vowel as long as possible, in order for the whole phrase to ‘read’ for the listener. All this is made that little bit more challenging by the big jump from high to low and the rising melody.

It’s the sort of thing you work really hard to get right in preparation and rehearsal then try to forget in performance so you can be ‘in the moment’.

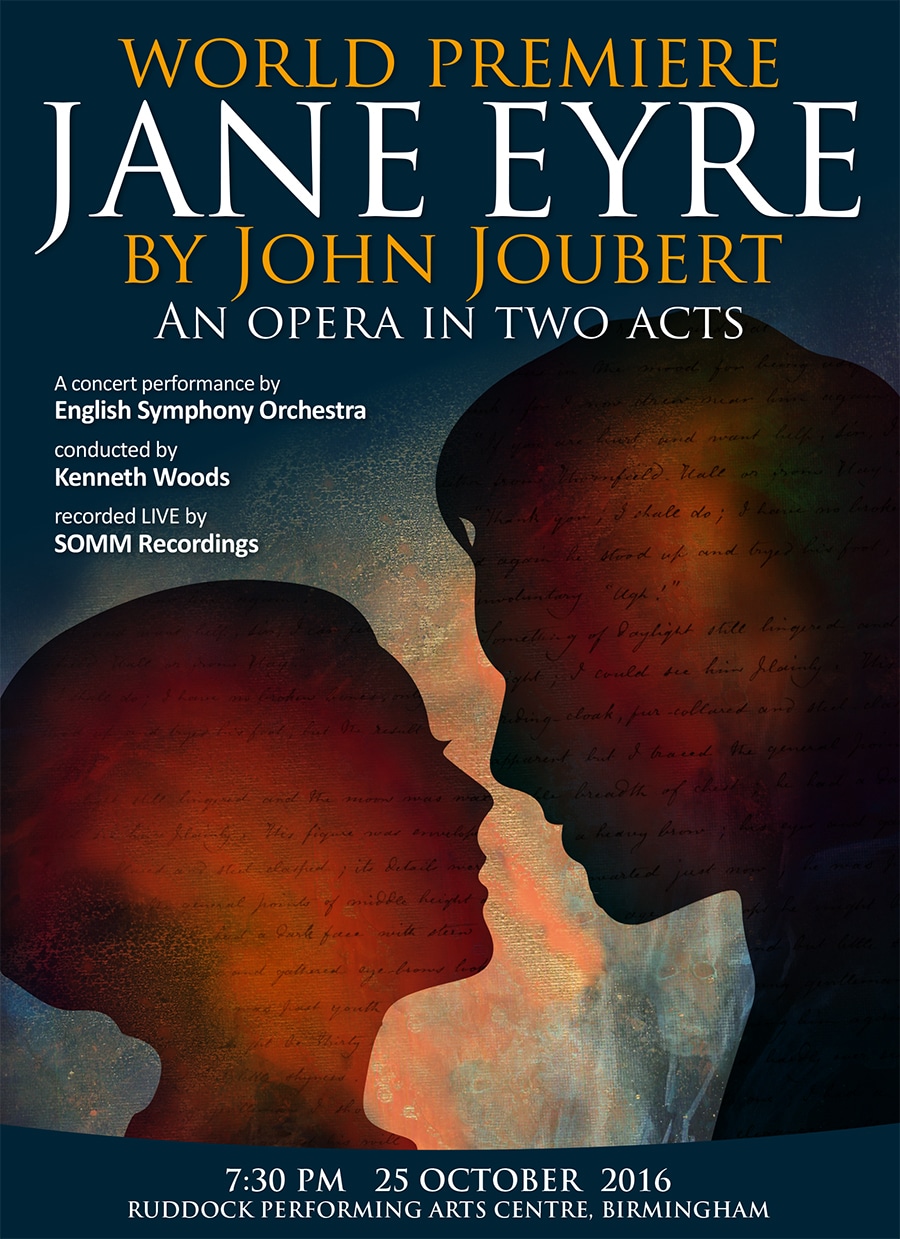

The richness and intricacy of this text means there is so much to bring out, so many cross-references and layers, internal rhymes. For a singer-poet, it’s pure bliss. With less than a week to go, I’m heaving, plaiting and sand-whispering at warp speed.