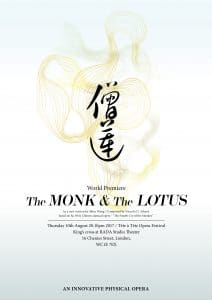

Since May, I have been involved in an extraordinary project: Monk and Lotus, a new opera mingling Western and Chinese opera and physical theatre. Below is a little taster of the result:

Whole-Body Singing: Shiru’s Wang’s Quest

Mapping the Petals of the Lotus

Lily feet: self-maiming as sexual fetish

On being reborn

Lily Hands and Phoenix Eyes: A Primer of Chinese Opera

Sound in Movement: Physical Theatre in Opera

Wobbling while Warbling: on balance or the lack thereof

Support Plus

The Soul in the Hand

X Marks the Spot: Honing Stagecraft

Finding Our Way

Whole-Body Singing: Shiru’s Wang’s Quest

The project originated five years ago in the mind of director and librettist Shiru Wang, a wonderful Chinese tenor who has sung main-stage Western roles for China’s finest opera companies for nearly ten years.

The audition notice spoke of his long consternation with the way that Western opera failed to use the full expressive potential of the body, and impetus for the project arose when he began to wonder what would happen if a production infused the movement and physical integration inherent in Chinese opera into the musical and psychological complexity of contemporary Western opera.

Stemming from the fundamental use of core muscles in Chinese Opera, he began to research the way that elements of physical theatre used by opera singers could enhance both support and the expressive potential of the drama itself. This has been the subject of Shiru’s Masters at East 15 Acting School, recently voted the UK’s most diverse acting school, and Monk and Lotus is his final project.

Two years ago, he chose a text: a classic Ming Dynasty tale called Zen Master Yu’s Dream in the Green Jade Land, a tale of a virtuous Buddhist monk, Yutong, who refuses to bow the knee to the newly promoted magistrate Liu. In revenge, Liu sends his courtesan Honglian, Red Lotus, to seduce Yutong and therefore ruin his credibility, promising her freedom for success. At its heart, it is a clash of physical and spiritual desire, an exploration of appearances and realities. It is also a question of what happens when our assumptions and selfishness are challenged by someone from an utterly foreign background and experience.

Shiru has lived with the story ever since, evolving a rich, multi-layered interpretation which he used as the basis for his libretto, which he gave to Niccolo Athens, an American composer living in Shanghai with long experience of composing on Chinese cultural elements and incorporating Chinese musical traditions.

The resulting score is extraordinary, fiendishly detailed in its psychological precision, alternating between the sage meditation and advice of Yutong to the coquetry of Lotus, spiky and lyrical in turn, with some gorgeous melodies and moments thrown in as they wrestle in their opposing intentions and desires.

Mapping the Petals of the Lotus

My character, Honglian or Red Lotus, is wonderfully complex. Having worked her way up from ‘barracks tramp’ to high-class courtesan, she is determined to use any means necessary to secure her freedom from a life of what is essentially gilded sexual slavery. Though she knows that what she has set out to do is wrong, what she herself names ‘an appalling act’, she is not precisely a ‘prostitute with a heart of gold’ but rather a deeply ambivalent young woman caught between her conscience and the dangled carrot of self-determination. Hers is a quandary a man would never face…

Lily feet: self-maiming as sexual fetish

One of the big themes of the opera is ‘lily feet’, also called ‘lotus feet’, or the custom of foot binding which was very common in Ming Dynasty China among high-class or upwardly mobile women, and which lingered into the twentieth century, though it is quite rare now. The process began as a young girl and was essential an act of self-maiming (usually aided if not initiated by a parent or guardian), involving the forcible constriction of foot growth and the folding of toes under the foot so that the foot was an ideal 4 inches in length. The result was a walk with a marked sway of the hips which men found highly erotic. It was also life-long disability.

Lotus sings frankly about this horrific experience, about the pain and the fear and the isolation, despising her sex for descending to what she calls a ‘wretched ruse for ensnaring men’ while at the same time choosing to use the very result of this pain—her ‘lily feet’, as one of her myriad of tools to arouse and seduce the hitherto impervious Yutong. It is one of the moments in the opera where she steps out of the character of the ‘shy viper’ (more about this later), giving us a glimpse of the grim reality which has shaped her and why she is so very desperate to escape it.

On being reborn

One of the other major themes of the work is that of illusion versus reality, between what the Monk shows Lotus to be her obsession with appearances and reality of the fleeting nature of earthly life. In turn, she shows him the hollowness of rigid religious asceticism, the self-deceit that is possible even at the height of self-controlled outward holiness.

In one version of the story, she is an actual lotus plucked from the heavenly pool of Guanyin, the Bhodisattva to whom Yutong’s temple is dedicated, and sent to the world of mortals. Through the course of the seduction which forms the central narrative spine of the opera, she comes to respect Yutong and thus despise herself for being the means of his undoing, even if she feels it is the only way to escape a life she now sees to be intolerable. Her profound self-realisation as a result of seeing the effect of her actions on Yutong—and his attitude towards her, notwithstanding those actions—fundamentally transforms the nature of the freedom she thought she had gained.

In that same version of the story, her epiphany restores her directly to the heavenly realm. One version of the story ends with Yutong committing suicide; another ends with him marrying Lotus, another with him putting aside his monk’s robes to become an ordinary man. Our version is much more ambiguous, but what is certain is that the encounter changes both of them forever, and traumatic as it has been, does so for the good. The themes of self-sacrifice, of the transformation of darkness to light, emerge in surprising and moving ways in the very midst of the murky circumstances. On the face of it, she is a sort of Chinese Lulu, the exquisite and terrible product of her experiences. But instead of meeting a Dr. Schön, just another man who will use her and whom she will use in return, she meets Yutong, a man of genuine character, even if flawed, and that makes all the difference…

Lily Hands and Phoenix Eyes: A Primer of Chinese Opera

As I’ve said, the heart of this project is a truly ground-breaking fusion of elements, finding a way to meld aspects of Chinese opera with physical theatre and Western contemporary opera to devise a compelling dramatic and musical work.

Coming into this project, I had absolutely no experience of Chinese opera. After some all-too-short tuition on its intricate language of posture and gesture, first with our assistant director July Yang and later with the wonderful Katie Lee from London Jing Kun Opera, I well understand how singers spend a year just learning to walk and many years to master fluency of it! From ‘lily hands’ (the basic on-stage posture for women) to the varied walking stances of different classes of women to ‘cloud hands’ to ‘phoenix eyes’ (a gesture denoting purity and respect of male authority) to the precise details of how to point (more complicated than you might imagine!), the possible combinations had my brain was leaking out of my ear by the end.

Even now, I am all too aware that I have only scratched the surface of the incredible richness of this tradition. As a western singer, I will struggle to approximate the ‘yun’, or ‘bearing’ which characterises the innate movements of an ethnically Chinese singer or dancer. I have lost count of how many times Shiru has demonstrated a seemingly simple gesture which, on further examination, is the synthesis of many layers of cultural aesthetic, a skin in which it is deeply challenging to feel comfortable.

But luckily for me, we are not attempting to demonstrate authentic Chinese opera! Instead, what we are attempting is an ambitious synthesis of traditions which respects and balances each element, a task that often involves the resolution of aesthetic clashes. One challenging elements in our synthesis have been the tradition of walking in semicircles as versus straight lines–a fundamental difference of approach and aesthetic, as I’ve discovered—and the sophisticated use of imaginary space due to the absence of props, involving a highly stylised use of gesture to mark out the narrative geography. To get this into our bodies, the dance studio floor pounded for days to the synchronised rhythm of our steps as we rehearsed our ‘Suzuki’ walk as a company, drilling the position of shoulders, hands, hips, feet, and use of core.

Possibly the most challenging element of this fusion is what I have come to call the ‘shy viper’: the fact that no matter how proud or inwardly brazen a heroine is, she still appears shy to men—indicated by a whole element of gestural language and postures, from the demure hand shielding the face to the perpetual 45-degree face tilt. The ‘prey’ is kept in the peripheral vision, reactions closely tracked, while still maintaining the façade of virtue.

Sound in Movement: Physical Theatre in Opera

For some time now, I have become increasingly convinced that physicality is central to the expressiveness of singing, that standing stock still while singing is deeply unnatural. More and more, I move as I sing, and relish the chance. As such, being involved this production has been a bit of a dream come true for me. It has also pushed the boundaries of my practice immensely and increased my respect tenfold for the physical capabilities and prowess of trained dancers and physical theatre actors such as Max Percy and Margherita Deri, the Monk’s and Lotus’s Shadows.

Wobbling while Warbling: on balance or the lack thereof

I am now an expert in the field of what I call ‘wobbling while warbling’, or the exploration of balance or the lack thereof while singing! We have had the luxury of ample rehearsal time to devise movement and explore a wide range of gesture, and though I have often come face to face with my physical limitations, it has been pure joy to extend my sense of what I thought physically possible for me by leaps and bounds—in some cases quite literally!

Never before having been able to indulge my ‘inner dancer’ to such an extent on stage, I am now utterly sold on the huge, almost exponential leap in expressiveness which this exploration adds to the performance. If all opera involved such insightful, nuanced use of the body, how differently we could engage new audiences…

Support Plus

One of the main avenues of Shiru’s research has been the way in which physical theatre can be used to enhance both vocal support and dramatic impact. In Monk and Lotus, each of the singers has a ‘shadow’ physical theatre actor who combines the roles of conscience, secret self, animal companion, dance partner, and giver of physical opposition and antagonism in moments of high drama.

We have tried to draw upon the wide vocabulary of movement available between the several traditions represented in our cast, and the results are often visually stunning. We sing back to back, standing up and down, bent over with our shadow on our backs, giving and taking our full weights, intertwined and mirroring or utterly at physical odds, depending on the juncture of the story. I certainly never knew it was possible to sing in such positions and postures. In one devising session, I sang a full-voice phrase while supported in a plank on Margherita’s up-extended feet. At one moment which has made its way into the final version of the show, I sing a passage on my knees while Margherita supports my back in a half head-stand!

The Soul in the Hand

In one memorable phrase from rehearsals, the ‘shadows’ become ‘the soul in the hand’: a physical extension of the self, but with heightened senses and sensibilities, able to transgress the usual physical boundaries and portray the inner conflicts and subconscious narratives of which the actual characters may actually be unaware.

The relationship of Monk to his shadow and the Lotus to hers is very different, and we’ve had great fun hammering out intentions and the minutiae of how each interacts—and how and when the shadows interact with one another.

X Marks the Spot: Honing Stagecraft

I can honestly say that no project I’ve been involved with has honed my stagecraft to this extent. The combination of music written to match and portray a specific psychological journey, movement crafted to match the precise timing of the music, and very precise staging has challenged my sense of spatial relations, making me immensely more aware of the difference a foot in one’s point of arrival can make in the eventual unfolding of an entire scene.

The other huge theme that has emerged through rehearsals in the integral importance of intention: why do we move? What motivates us? No gesture or movement should be made for the sake of it, but should emerge from the thinking and desires of the character. Just as movement should stem from the core muscles, so it should stem from the emotional and psychological core. It sounds self-evident, but I’ve found it amazing how easy it is to move without intent, how awareness of each movement is a skill that must be carefully cultivated.

I would imagine that this is the way that theatre actors work all the time, but I can certainly say with chagrin that nothing in my conservatoire training, and little in my experience of blocking in opera to date, prepared me to work in such detail and discipline as this. What a wonderful rigour to experience now…

Finding Our Way

I love the fact that this project is deeply experimental. It is very much a work-in-progress, a matter of finding our way through unmarked territory. I am incredibly privileged to be able to give Lotus both motion and voice for her first emergence in this form. I hope that, in addition to our 8 London performances over the next month and a half, Monk and Lotus travels far and wide, as indeed its component influences already span three continents, both East and West.

Performances:

Monk and Lotus

An innovative physical opera

10 August, Tête-à- Tête Festival

RADA Studios, 7:30pm

11,12, 14-16 August, Grimeborn Festival

Arcola Theatre

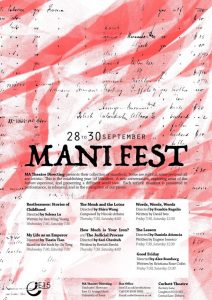

28, 30 September, Manifest Festival

E15 Acting School, IG10 3RY