‘For we shall be hereafter as though we had never been’.

Cheery thoughts from Solomon, he of the Ecclesiastes quote, ‘Meaningless, meaningless, everything is meaningless!’ One could imagine that in a song-cycle with a title such as Songs of Loss and Regret, these themes would mount in an ever-ascending spiral of cynicism and despair.

But I would say that the same rather applies with SoLaR (as we’ve christened it) as to Shostakovich’s Symphony 14, of which he said, ‘My symphony is an impassioned protest against death. Death is terrifying; therefore, live nobly’.

As a practising Christian, I have a specific set of beliefs about suffering, death, and the afterlife, but it has been a fascinating process to sit in another seat for a while, to see all these fundamental issues and questions from a rather different angle, to ponder and attempt to embody what it would be like to not know…

Working on this song-cycle, with all its echoes of World War One, has also thrown up many parallels to my Masters and doctoral research on WWI poet and composer Ivor Gurney. I also think it’s a marvellous piece full of detail worth noticing, and that it’s very relevant for where we find ourselves as a culture, so I have a great deal to say about it.

What follows falls into several parts:

a. Background about the historical context of Sawyers’ ‘musical language’

b. A brief discussion of the tools he uses

c. A song-by-song exploration of how he uses them, highlighting my favourite bits along the way.

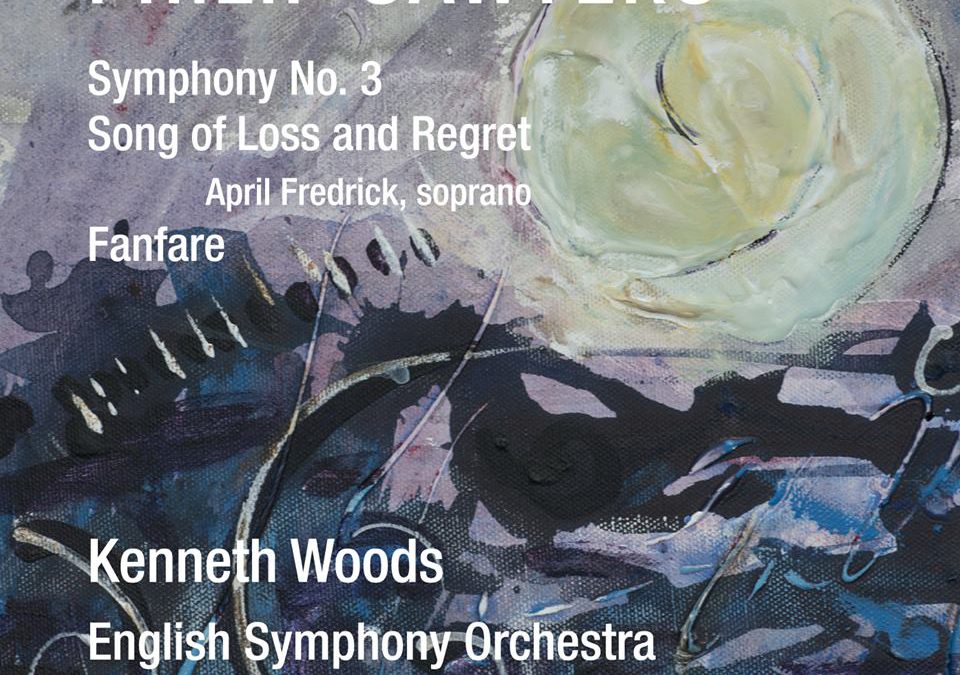

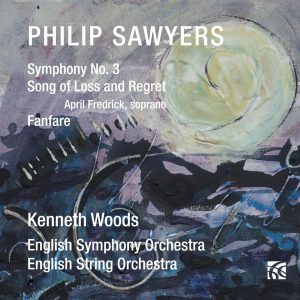

I guess I’ve designed it to be read alongside the recording (which, helpfully, doesn’t come out in full until the autumn!), so if you can’t make it along to tomorrow’s performance, on 28 February at St John’s Smith Square, several sample movements from the recording are available on YouTube below, so do compare notes—and see if I put my ‘vocal money where my mouth is’ and do as I say!

I’ve tried to explain technical musical terms for those not familiar with the jargon, and I have tried to only include things I thought would be interesting, but as I’ve lived with this piece for a year and half now and see more in it than ever I did, I think that a ‘geek-alert’ is definitely in order! So stay with me if you will or feel free to skip to whatever interests you most.

Sections

The Land of Lost Content: Musical home and how we left it

The Breaking of the World

Tools of the Sawyers trade

Circumventing Solar

1. A Shropshire Lad

2. More Poems XL: Farewell to a Name and a Number (A.E. Housman)

3. More Poems XXXVI: Here dead lie we (A.E. Housman)

4. Break, Break, Break (Alfred Lord Tennyson)

5. Futility (Wilfred Owen)

6. From ‘Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard’ (Thomas Gray)

7. The Wisdom of Solomon (The Apocrypha)

8. Song from The Earthly Paradise (William Morris)

The Land of Lost Content: Musical home and how we left it

It is perhaps no accident that we begin with regret, with a rückblick, or backwards look over the fence of the past to the ‘land of lost content’, to ‘the happy highways were I went / and cannot come again’.

Much of western ‘classical’ music is built on the ‘tonal’ system, the idea that all music precedes from and longs to return to a single note with an almost gravitational compulsion. Even in the Middle Ages, before this system evolved ‘modes’ functioned in the same way, and the same principle (albeit in different manners) applies to the ragas of Indian music and to the folk music of many cultures across the world.

What can be more ancient than departing and returning to the place of departure? Of journey and home-coming rendered in sound? But this system of departure and return was eroded in small and great steps over the course of the 17th-20th centuries and finally, with a great groan, seemed to give way all together at the beginning of the 20th.

The Breaking of the World

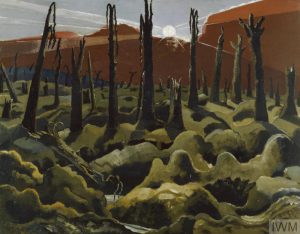

It is convenient to see the Great War as the symbolic Breaking of the World. It began before, of course, but it is hard to overestimate the manner in which the War to End All Wars shook Europe to its ideological core, shaving off the final threads of the screws of certainty in many ways and fields, not just in music (for music merely reflects in sound the thoughts and priorities of a culture).

Enter Schoenberg, at the end of a long line of pushers of boundaries, with his initial theories of atonality (music which could function without a fixed tonal centre), later developing the 12-tone system which did away with the idea of a ‘home note’ all together in favour of something much more logical and mathematical, avoiding ‘consonance’ and aiming for dissonance. Down with sentiment, he seems to say. The old ways are dead. Let us think anew.

In this song-cycle, exploring the still-raw wound of WWI a century later, Sawyers draws on all these traditions and influences, maintaining a tonal centre but skilfully utilising elements of the ‘musical language’ of Schoenberg and other defiantly ‘modern’ composers to create an ever-shifting psychological palette, simple yet devastating.

Tools of the Sawyers trade

Sawyers’ mastery of musical psychology is immediately evident from the first bars of the cycle. What are his tools?

A semitone (half-step) up or down in a melody or within a chord raises the hopes or dashes them, moving the affections this way and that with Bach-like precision. We sink ‘chromatically’, semi-tone by semi-tone as though into the depths without end. We oscillate between major and minor in tiny but telling gestures. ‘Tall chords’—7ths, 9ths, 11ths, and even 13ths, piling third upon third above the ‘root’ chord and configured in wide-flung and deliberately obscure voicings, obscure the tonic or ‘home’ note.

He also makes great use of fourths (think ‘here comes the bride’), often many of them in a row, often in a ‘melisma’ (many notes on one word or syllable) as both a ‘heroic’ and ironic gesture. Is he referencing the music of the trumpet summoning soldiers to battle or directing them in the course of it? To me as the singer, these passages feel a bit like running up a really steep hill, engaging the vocal ‘quads’, as ‘twere, blowing the top off ‘polite’ narrative—yet again. Grief knows no etiquette…

Circumventing Solar

‘A Shropshire Lad’ (A.E. Housman)

We begin the entire cycle with a ‘fully diminished’ B minor chord. It’s a standard triad (the tonic plus a third and a fifth above it) collapsed inward as far as it can be without ceasing to be a chord at all. I used to think of it as the ‘utter tragedy’ chord (usually preceded by a ‘half-diminished’ chord), of the sort used to signal in a film that the worst possible scenario just became reality. And this is just the first chord!

Nearly every word contains a tonal ‘tweak’, a move to mirror the words subtly or dramatically. Listen to what he does in passages like ‘from yon far country blows’. Where is home, Sawyers seems to ask with all these ambivalent, shifting harmonies. Did we ever know? If we did, we cannot go back. ‘What spires, what farms are those?’, the poet Housman asks, Sawyers ending the line with a little chromatic twinge. Once, he knew them intimately, but now they seem an utterly foreign realm. Which of us has not had that sensation when revisiting the scene of a happy childhood memory? Everything seems smaller, less vivid, like a toy world. For we have been changed by what has passed since.

He returns to the opening material, setting up the astonishing chord change (so simple yet so powerful) on the final word of ‘The is the land of lost content’. Whew! It’s like hearing the air hiss out of that balloon: all flights of fancy grounded. From A major to Ab minor may not seem like a big leap, but to the gut, it is.

‘I see it shining plain’ is one of the few resolutely major passages in the entire cycle, to be sung (I reckon) with radiant face. But coming back down the mountain, the glory fades. The harmonies return to that of the second bar (flattened, sombre), rising for a moment (will those days return?) on ‘The happy highways where I went’, and Sawyers uses this gesture over and over again throughout the cycle, both ways. Rise, return to hope: move up a semitone. Move back down by semitones, deflating like a beached hot air balloon

Then comes one of the most twisty, chromatic passages of the work in the orchestra, also rising to some of the highest pitches of the work, as if the pain accompanying the beauty of those memories stabs him full deep before subsiding to a resigned, quiet ending on ‘and cannot come again’, full of hollow chords without the 3rds that would ground us in either major or minor.

2. More Poems XL: Farewell to a Name and a Number (A.E. Housman)

This is a truly gutting lament for the way in which war reduces a beloved human being to a mere statistic: ‘Then ceases and turns to the thing he was born to be / A soldier cheap to the King and dear to me’. I’ve got to nearly spit these lines out, halfway between rage and that stomach-churning cry specific to grief. What else is there to do?

So many beautiful gestures—where do I begin, and where end? Personal favourites: the twisty opening motif (picked up in later movements), like an audible exhalation of anguish, the almost lullaby-like oscillating chords on ‘darkness’, giving way to the raw, hammer-like blows of ‘in blood and pain’. The almost optimistic harmonies on ‘the flaming flight of valour’ deflated by those lowered semitones on ‘and truth’ (so incredibly wistful), the regal melodic line of ‘returning’, with the slow chords underneath ‘to dust and night’ to give us time to register the body of the beloved (if there was one) lowered into the ground, to absorb the horror of it.

3. More Poems XXXVI: Here dead lie we (A.E. Housman)

Somehow as I begin this I always hear the bit in The Fellowship of the Ring where the Nazgul asks directions to Frodo’s home in Bag End: ‘Shiiiiiiiiire, Baaaaaaaagins’, the sepulchral voice intones, the flesh shrinking at each syllable. As Aragorn says, ‘they were once men’. Unlike the Nazgul, whose greed occasioned their fate as wraiths, the soldiers’ only sin was that ‘we did not choose to live and shame the land from which we sprung’.

All the peer pressure to join, all the inflated threats of an inhuman enemy and promises of a swift victory, the flower of an entire generation wiped out in one fell swoop. Did it all boil down to shame?

Sawyers uses a dirge-like downward tread in the lower strings with slow-moving chords to portray the progress into Hades. Personal favourite: What he does on ‘lose’ in the line ‘Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose’, with a change of chord and suspension (the holding-over of a note against a chord change so we feel that ‘crunch’ before a resolution which releases the tension). It’s almost visceral. Wow.

Then a brief glimmer of light on ‘but young men think’, subsiding back into shadow on ‘it is’, before the upward melody in the strings, like a gathering up of courage to speak, flows over into the blazing-eyed spectre’s aching challenge: ‘and we were young’. Then the dirge resumes, the spectres return to the grave, and we are left hollow-eyed and shaken at the sheer waste of it all.

4. Break, Break, Break (Alfred Lord Tennyson)

Here we leave Housman and the ‘blue remembered hills’ for the rugged seascape of Tennyson. And here we emerge into the angry stage of grief, when the poet invokes the sea to rage and beat, wishing he could be as eloquent in his grief. He considers others’ happiness (the fisherman’s children playing, the sailor singing in his boat) with the bereaved’s sense of effrontery that anyone’s world dare go on as before when his is shattered.

He subsides into reverie as he contemplates the fate of all: ‘And the stately ships go on / to their haven under the hill’ and then the loss of his own light. One of my personal favourite moments in the piece is the rocking harmonies on ‘But O for the touch of a vanished hand / and the sound of a voice that is still’ (not unlike ‘Darkness and silence’ in ‘Farewell to a name and a number’). Then back to fury and waves, with one final caress of the memory of the beloved.

5. Futility (Wilfred Owen)

Oh my. The very thought of this one gives me goosebumps. Maybe I shouldn’t admit to having a favourite song in the cycle, but this is definitely it. In some ways I feel as though it’s the epicentre of the cycle, a perfect jewel of wringing loss: because the beloved isn’t actually dead but might as well be.

This is a portrait of acute shell-shock, sending out a hale and hardy farm boy with the seasons and rhythms of the land in his body and blood and receiving back a living corpse, mind shattered from the ceaseless bombardments, lack of sleep, mud, and cold, the horror of seeing comrades smiling and joking one minute reduced to unrecognisable mush the next.

And this was the view of a soldier and a poet: Wilfred Owen. I am reminded of the comment by Winifred Gurney (the sister of Ivor Gurney) about the folly of sending artists like her brother to war: ‘To think of the “Military Machine” sending out that “sensitive plant” to the mire of Flanders Fields makes my gorge rise even today.’ She also recalls the words of her husband, who also fought in France in WWI:

‘Even the ancients of old had more sense than to send their poets and musicians on to the battlefield. They sheltered them so that they could tell of events in verse and song for the benefit of posterity. We so-called civilised people cast our pearls before swine. May God forgive us’.

One could say that their presence there was hugely important, showing us what really happened, what it was really like, that only a poet who had seen the realities of France could have written ‘Futility’, but still, what an indictment…

I would say, from the way that Sawyers set the poem, with such tenderness, that he must feel equally as strong about it. The strings rock us like a baby throughout, perhaps mirroring the unseeing rocking of the soldier in his invalid chair, on the porch. Little semiquavers (16th notes) in the violins stir like a breeze and subside in the face of such suffering.

We begin low in the range, with melodies within a small compass, almost whispering like the family discussing what to do with the soldier, building into notes and volumes as the poem progresses to ‘If anything might rouse him now’, dropping back down to the original phrase on ‘the kind of sun will know’.

We return to the same music for ‘Think how it wakes the seeds / Woke once the clay of a cold star’, like the family telling themselves things are bound to look up, daily searching for signs of recovery, of the son, brother, husband they knew and loved in the face of this stranger. ‘It has always worked before. The sun is the source of all life. Surely, surely…’

Owen rises to the great outburst on

Are limbs, so dear-achieved

Are sides, full-nerved, still warm

Too hard to stir?

Was it for this the clay grew tall?

Sawyers sets this section in great chords moving in parallel downward motion with surging upward semiquavers from the lower strings, this contrasting motion between voices like an internal revolt against such a fate.

The ‘breeze’ semiquavers bring us back down to the final weary question: ‘O what made fatuous sunbeams toil’, subsiding to the original music for ‘at all’, repeated, ever more wearily, four times, as if watching the final drawn-out breath leave the soldier. What a song.

6. From ‘Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard’ (Thomas Gray)

Despite having no obvious military connection, this song begins with a spiky dotted motif which manages to feel rather ‘military’ as well as evoking ‘the boast of heraldry, the pomp of power’ with which the poem begins.

It also has lots of links (it seems to me) in both theme and motif with ‘Farewell to a name and a number’. Even that opening motif, with its jagged great leaps and jarring tri-tones (either a 4th raised a semitone or a ‘squished 5th’, referred to in olden days as ‘the devil’s interval’), signal that all is not well.

And perhaps Sawyers is signalling, too, that it is that very boasting of pomp and power which gave rise to the willingness of the British ‘Military Machine’ to send its best and brightest (and indeed anyone at all) to be machine-gun fodder, mere collateral damage.

The dotted rhythms evoke both stiff Baroque monarchs in their silks and jewels and snappy soldiers marching along in straight lines and crisp formations. All ‘await alike the inevitable hour: the paths of glory lead but to the grave’.

The next section, with its rhetorical pleadings as to whether subsequent remembrance of glory is any substitute for the living, loved person has wonderfully ironic, almost sea-sick alternations between semitones on ‘animated bust’ and ‘back to its mansion call the fleeting breath’, almost taunting the reader for an answer none can give.

Favourite moment, without question: ‘the dull, cold ear of Death’, twice intoned with suddenly slow, threateningly smooth rhythms, all jaggedness—signs of life, after all—giving way to the permanent inertia, the frozen stare of surprise in the face of mortality. Those slow notes give me plenty of time to play with the vowel quality and sound to get the full weight of the dramatic gesture.

7. The Wisdom of Solomon (The Apocrypha)

It begins innocently enough. A slower dotted motif in the violins with nudging movement from below, first up, then down, like a plane skimming low over hills—or like smoke or mist hugging the slopes before burning away.

The first phrase ‘For we are born at all adventure’ is nearly echoed in the second—till we encounter the fateful lowered tones in ‘hereafter’, a pattern that continues into the incremental rise of ‘never’ and the sinking back down of ‘been’; such a simple gesture, so effective.

The next two phrases, again, begin in a similar fashion and only a semitone apart but end differently: perhaps mirroring the parallelism so characteristic of Hebrew poetry, stating the same idea twice in slightly different ways.

First the dramatic statement: ‘For the breath in our nostrils is as smoke’ (again with all those little semitone tweaks up and down which give it punch and force), a sentiment extended and underlined by ‘and a little spark in the moving of our hearts’.

And then another masterstroke: the chords oscillating in semitones, churning like something from a horror film under ‘And our name shall be forgotten in time, and no man shall have our works in remembrance’. What an awful thought, brilliantly set.

Then Sawyers eases into the stillness and relative serenity of

And our life shall pass away as the trace of a cloud,

And shall be dispersed as a mist

That is driven away with the beams of sun’.

These is definitely one of my favourite lines in the piece (they give wonderful scope for great vocal colours and shaping).

We then resume our ‘bird’s-eye view’ hill-skimming motif from the opening (and much of the same melodic material) on ‘For our time is a very shadow that passeth away’, with the lowered semitones of ‘hereafter’ (oh the world-weariness!) recurring ‘and after our end’, ending on the same note-and-gut contraction ‘there is no returning’ as on ‘as though we had never been’. ‘For it is fast-sealèd’ echoes ‘For the breath of our nostrils is as smoke’, finished in the whisper: ‘so that no man cometh again’, echoing end conclusion of ‘The land of lost content’.

8. Song from The Earthly Paradise (William Morris)

In some ways, this is one of the most cinematic of the songs, also the first to mention God in any form.

We begin with a long melisma on ‘O brooder on the hills of heaven’, with ‘brooder’ and ‘hills’ elongated as with a panning camera angle of the enigmatic figure in the mind’s eye. The jagged figure of fourths first heard in ‘and we were young’, ‘shall flattery soothe’ and ‘and our life’ is used over and over in this movement, each time over a slightly different accompaniment, as the poet recalls the moment Adam and Eve (and each of us) was cast out of Eden and why: ‘when for my sins thou drav’st me forth’.

Like a thought we can’t kick, that dog-and-bone fear or regret or grudge, mulling over our failures and building a case against God for allowing such a flawed world to exist. The effect is incredibly restless, a sort of ceaseless harmonic searching but without resolution.

The poet stops for a moment to lodge his great existential objection: ‘Hadst thou forgot what this was worth, Thine had had made?’ before resuming his search. Indeed, we speed up, a ‘walking bass’ in the lower strings against a fluttering semiquaver motif in the upper strings driving us ever forward as the poet casts up more sorry facts of life on earth:

The tears of men,

The death of three-scores and ten,

The trembling of the timorous race

Like evidence in a courtroom with God in the dock. The poet asks if grief, suffering, death, war and oppression have so marred the world God created, ‘had these things so bedimmed the place / Thine own hand made’ that he has rejected it. In his desperation he has repeated ‘Thine own hand made’, incredulous that a Creator could really reject and forget his creation thus.

Then the poem turn from prosecution to pleading with God that there is yet good, unimaginable good, which could yet arise on earth, were fear ended and hope and love to remain. He says,

Thou couldst not know

To what a heaven the earth would grow

If fear beneath the earth were laid

If hope failed not nor love decayed.

This hinge-point has obviously moved Sawyers, as the semiquavers racing forward in intensity and urgency and he sets ‘To what’ three times, building up to ‘to what a heaven the earth would grow’ (italics mine). The motif after this statement is so wistful, and so lovely, so simple and innocent, it rends the heart.

We return to the opening motif before the all-important statement of what would shift the balance of all this misery: ‘If fear beneath the earth were laid’: not men killing one another, not illness laying low young and old alike, but fear itself buried once and for all. If what we hoped for really did come true and selfishness and time did not dim love. If only…

One could say that according to the Christian view of the world, many of these things do occur. God Himself enters into His creation in the person of Jesus, experiences suffering with us and continues to plead our case before the Father. John says that ‘perfect love casts out fear’, and Paul says that ‘our hope does not put us to shame’, that ‘Though outwardly we are wasting away, yet inwardly we are being renewed day by day’.

The question, I suppose, is our understanding of what divine presence and redemption would look like. Politics and goodwill fail us eventually—a truth we feel more keenly than ever at this juncture in history, our good intentions dissolving into more fear, and war and death. Morris feels that the mere existence of suffering and death means that God must have abandoned the earth.

Interestingly, the Christian faith says that meaning and hope and peace can be found amidst suffering, sometimes even because of it, though that process is never simple or easy. I have certainly found it to be so, though I have certainly not suffered as many have, these poets included.

But our collective attitude towards faith has, like tonality, has been worn down and beset by many foes these past years, and many are left with the same ambivalence, wishing to believe but unable, longing for home but uncertain where to begin.

And yet, somehow, even ending on the word ‘decay’, spelled with hollow harmonies and no ‘root’, Sawyers manages to finish with something approaching hope. Even the memory of hope and love, that glory of the human race, makes the entire struggle to retain and increase it—all the loss and regret—fully worth it.